Part 1: The Site of Special Scientific Interest

Croham Hurst was, at my suggestion in the 1970s, declared as a statutorily recognised Site of Special Scientific Interest, on the grounds that it is at least in part ‘ancient woodland ‘ and that it has a high degree of species diversity (that is, many more species than found in Littleheath Woods, for example). These factors reflect the ‘ancient’ status of the woodland, and also reflect the three contrasting subsoils.

Crucially, also, the woodland is almost exclusively a natural development over the centuries, although two groups of pine trees have evidently been planted, by whom and when and

why is not known. These alien trees are now valued locally as one of several archaeological and historic features which add to the overall cultural value of the Hurst. The natural status is, regrettably, threatened by recent misguided deliberate planting of garden daffodils, and by invading species brought into the woodland margins with illegally dumped garden waste.

The natural status of the Hurst embraces the effects of entirely natural events, such as the storm of 30 May 1903, the devastating ‘Surrey hailstorm’ of 16 July 1916 and the ‘Great Storm’ of 15/16 October 1987 which many of us of course remember. Occasional events of that nature have been a part of the evolution and regeneration of Croham Hurst since the woodland first developed. The 1987 storm was in fact good news for the biodiversity of the site, as so many trees falling allowed light into newly formed glades, and extended such valuable habitats. Fallen trees, other than those posing a danger to the public or obstructing footpaths, were deliberately left lying to become habitats for fungi and a host of invertebrates which flourish on or in dead wood.

‘Ancient’ woodland does not necessarily imply ancient trees. Over a century ago, when public campaigning defeated proposals to sell the woodland for housing, it was said that there were few or no trees on Croham Hurst more than a hundred years old. The point is that Croham Hurst has been, in large part, woodland continuously since at least as far back as the earliest known records. Relatively modern woodland, such as much of Bramley Bank, has far fewer species of plants and trees The contrasting subsoils support differing plant populations.

The mildly alkaline chalky soils around the woodland margins, for example, are favoured by wild clematis (Clematis vitalba), a climbing plant not to be seen on the sandy slopes or pebbly summit. Heather (Calluna vulgaris and Erica cinerea) on the other hand only grows on the acidic heathland soils on the pebble beds, as does bilberry (Vaccinium myrtillus). There are no really rare plants growing wild locally, although butchers broom (Ruscus aculeatus) and lily of the valley (Convallaria majalis) are relatively uncommon outside gardens. They appear to be genuinely wild, not garden escapees.

During the last 146 years members of the Croydon Natural History and Scientific Society such as William Hadden Beeby, Henry Franklin Parsons and Cecil Thomas Prime,have recorded plants and trees growing on the Hurst, including 17 kinds of trees, 24 shrubs, six climbing plants, 36 different grasses and sedges, just over 100 other flowering plants, and 15 cryptogams such as ferns. There are of course changes over time. In the 1830s Daniel Cooper recorded various wild orchids in and around the woods. All have long since vanished, many of them into Victorian botanists’ collections of pressed wild flowers such as held by institutions such as the Natural History Museum.

Juniper (Juniperus communis) also seems to have disappeared. There have also been gains. Those that have arrived naturally, including even Buddleia (a native plant in Chile), are welcomed as compatible with SSSI status. Looking forward, although Croham Hurst is natural woodland, not a park or garden, it is subject to some degree of management by, amongst others, members of the Friends of Croham Hurst Woods. Amongst their projects is care for the roadside bank along Upper Selsdon Road, which is home to a scarce plant, Pale St. John’s wort (Hypericum montanum). There are also attempts to maintain the small patch of grassland near the West Hill entrance. Open chalk grassland supports species not found in the woodland.

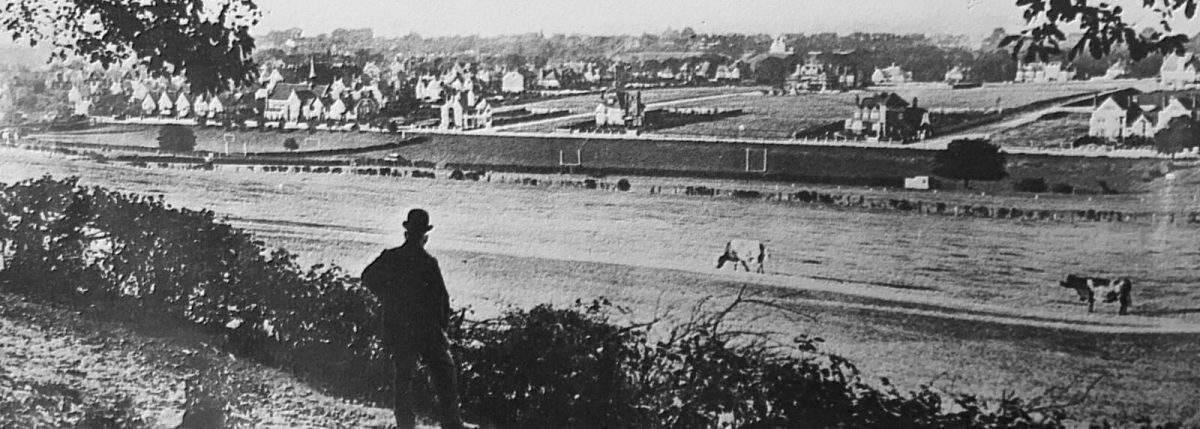

Other projects include protecting the heather on the summit, threatened by encroaching silver birch. Numerous surviving Edwardian postcard views show that this small patch of heathland was once so clear of birch that this was a much loved spot from which to admire the rural landscape (before all the houses) southwards to the crest of the North Downs

at Reigate. Even as recently as the 1940s, this was also a favourite spot from which to watch aeroplanes landing and taking off at Croydon Airport.

Compared with botanical recording, very little attention has been paid to the animal opulations on the Hurst, although here again a high species diversity (mostly invertebrates) probably also exists. Amongst the slugs and snails, for example, a good number of the 120 or so species recorded in Britain can be found in the woodlands. All of them are much smaller than the common garden snail, some not much bigger than the full stop at the end of this sentence.

Snails such as the rather attractive round-mouthed snail, Pomatias elegans, for example, can be found on the chalky soils but very few if any will be seen higher up the slopes. It isn’t laziness! Snails will not thrive so well on acidic soils, as they need the lime from chalky soil to grow their shells.

Reproduced from CVRA Winter 2016 Newsletter

The history of Croham Valley extends back around ninety million years, that being the approximate age of the chalk and its contained fossils of marine animals underlying so many of our gardens.

The history of Croham Valley extends back around ninety million years, that being the approximate age of the chalk and its contained fossils of marine animals underlying so many of our gardens. The middle layer of rock beds forming Croham Hurst is the Thanet Sand (named after the Isle of Thanet in north-east Kent where geologists first studied it). The sand forms the fairly steep slopes down from the summit ridge, and is most visible from the steps leading down Breakneck Hill towards Upper Selsdon Road, where from time to time heavy rainfall has washed some of it away, leaving several trees ‘standing on their roots. The name ‘Breakneck Hill’ has appeared on maps since at least as early as 1877, but there seems to have been no record found of when and why this name was adopted.

The middle layer of rock beds forming Croham Hurst is the Thanet Sand (named after the Isle of Thanet in north-east Kent where geologists first studied it). The sand forms the fairly steep slopes down from the summit ridge, and is most visible from the steps leading down Breakneck Hill towards Upper Selsdon Road, where from time to time heavy rainfall has washed some of it away, leaving several trees ‘standing on their roots. The name ‘Breakneck Hill’ has appeared on maps since at least as early as 1877, but there seems to have been no record found of when and why this name was adopted. The higher parts of the Hurst, at least, have apparently never been cultivated, resulting in the survival of archaeological evidence. The most visible feature is the tumulus, or burial mound, near the pine plantation on the eastern open heathland. This was identified by Sanderstead resident and archaeologist Brian Kenneth Hope Taylor [1923-2001] in 1946 on the evidence of a crudely worked Bronze Age flint implement kicked out by a burrowing rabbit. The mound, a Scheduled Ancient Monument, has never been archaeologically excavated. It is most unlikely to contain any recognizable bones or metal artefacts on account of the very porous and acidic soil. Nearby in the open heathland local archaeologist Peter Ladson Drewett [1947-2013] and other members of the Croydon Natural History & Scientific Society identified traces of temporary huts during excavations in 1968. The huts were perhaps made by charcoal burners. The last most visible man-made features on the hill are several old Croydon parish boundary posts, bearing various dates from 1888 to 1920. The significance of the dates is not certainly known. The north-west corner of the Hurst was in the historic parish of Croydon, the remainder in Sanderstead. At least one of these posts (dated 1888) is now missing, but who dug it up, when, and where it is now are not known. Anybody wanting to detect less obvious features can hunt for the at least three surviving Ordnance Survey ‘revision points. ‘These are small roughly circular blobs of concrete with OS and a number and letter code inscribed on them. They mark precisely mapped reference point positions surveyed to the nearest ten centimetres and are shown on Ordnance Survey 50 inches to the mile plans published in the 1950s. They are not now used as when OS mapping is revised, as most revision now is done by aerial photography. Vanished former features have been an ornate, probably early 20th century drinking fountain, a pond, and public lavatories, all near the Bankside entrance. There was, also, once a corrugated iron hut for an on-site park keeper. This was near the West Hill entrance.

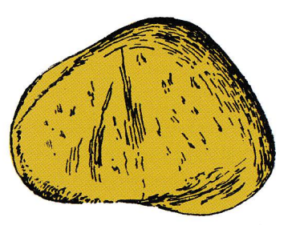

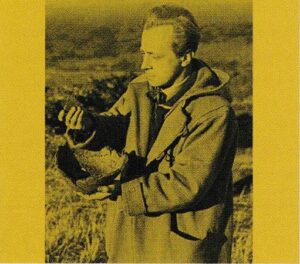

The higher parts of the Hurst, at least, have apparently never been cultivated, resulting in the survival of archaeological evidence. The most visible feature is the tumulus, or burial mound, near the pine plantation on the eastern open heathland. This was identified by Sanderstead resident and archaeologist Brian Kenneth Hope Taylor [1923-2001] in 1946 on the evidence of a crudely worked Bronze Age flint implement kicked out by a burrowing rabbit. The mound, a Scheduled Ancient Monument, has never been archaeologically excavated. It is most unlikely to contain any recognizable bones or metal artefacts on account of the very porous and acidic soil. Nearby in the open heathland local archaeologist Peter Ladson Drewett [1947-2013] and other members of the Croydon Natural History & Scientific Society identified traces of temporary huts during excavations in 1968. The huts were perhaps made by charcoal burners. The last most visible man-made features on the hill are several old Croydon parish boundary posts, bearing various dates from 1888 to 1920. The significance of the dates is not certainly known. The north-west corner of the Hurst was in the historic parish of Croydon, the remainder in Sanderstead. At least one of these posts (dated 1888) is now missing, but who dug it up, when, and where it is now are not known. Anybody wanting to detect less obvious features can hunt for the at least three surviving Ordnance Survey ‘revision points. ‘These are small roughly circular blobs of concrete with OS and a number and letter code inscribed on them. They mark precisely mapped reference point positions surveyed to the nearest ten centimetres and are shown on Ordnance Survey 50 inches to the mile plans published in the 1950s. They are not now used as when OS mapping is revised, as most revision now is done by aerial photography. Vanished former features have been an ornate, probably early 20th century drinking fountain, a pond, and public lavatories, all near the Bankside entrance. There was, also, once a corrugated iron hut for an on-site park keeper. This was near the West Hill entrance.